“I gave up on ever trying to get ‘my way.’ I barely knew it existed.”

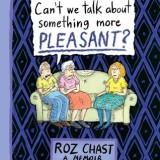

The year was 2010 and a truly great graphic memoir exploring loss and acceptance caught fire in reading circles everywhere. That grand achievement was David Small’s Stitches. Four years later, Roz Chast has something of startling profundity on her hands. Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant?, her graphic memoir, explores similar themes that Small captured, but Chast’s work seems deeper, richer, and even more alive.

Livelihood seems like the most unlikely of topics in a memoir that explores death so directly. In fact, Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant? opens with Chast asking her parents a question related to their unavoidable approaching demise. She writes, “So…do you guys ever think about…things?” The implication is, obviously, that something needs to be said about end-of-life plans. How do George and Elizabeth, her parents, feel about resuscitation? What measures do they want taken to sustain their lives? Do they have money? The inquiries are personal, but she is their daughter and needs to know. The remainder of the memoir tells the story of Chast dealing with her parents as they move from being independent (or codependent) to losing their physical and mental capabilities. Finally, she takes us into the very personal final days and minutes of both parents.

Chast’s memoir is an artistic collage of sorts. She writes, uses photos, and even inserts a few of her mother’s poems. Mostly, though, Chast draws. Her use of hues is splendid, with troubling moments losing their colors. The humorous scenes lighten up and make the pages pop.

This is not a saccharine story, one told to make familial relationships seem impossibly perfect. Instead, Chast writes with truthfulness that strikes hard. The relationship between Chast and her mother is far from perfect. Chast often draws Elizabeth as a large, overbearing figure, which captures the words Chast relates to her mother’s personality. Chast struggles to connect with her mother, although she tries on countless occasions. It’s never doubted whether the writer has respect and love for her mom; instead, we see a glimpse of a relationship with occasional arguments and disagreements—you know, a real mother-daughter story.

To capture her father, Chast draws George meekly and with a noticeably small presense, which, again, seems fitting to her words. Her connection with her dad is less strained, although it, too, has rocky parts. He worries and fears many parts of his life. His last months and days are especially difficult. A man prided on his intelligence, George loses his mental keenness. His decline is particularly difficult to bear not only for the author but for readers, as well. Chast writes, “After my father died, I noticed that all of the things that had driven me bats about him—his chronic worrying, his incessant chitchat, his almost suspect inability to deal with anything mechanical—now seemed trivial. The only emotion that remained was one of deep affection and gratitude that he was my dad.” Lines like this one occur in rapid succession.

Chast’s understanding of humanity and her ability to capture both its fragility and harshness are on full display in Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant?. To answer the title’s question, I guess we could, but it wouldn’t be as meaningful or important. This is literature.

Review: Can’t We Talk about Something More Pleasant? 5.00/5 (100.00%) 16 votes