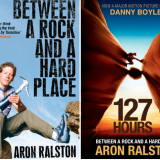

Between a Rock and a Hard Place, Aron Ralston

Positives

Negatives

Considering that: a) I already knew the full story of Ralston’s days trapped by a boulder in a remote canyon, b) I had already seen the brilliant 2010 film made of his experience (127 Hours, starring James Franco, a favorite of mine ever since his days as Daniel on Freaks and Geeks), c) this book could fall into either of the dodgy genres of celebrity memoir or jock’s adventure story, and d) the title is such a horrible use of a cliché, I wasn’t expecting this book to be the well-written and utterly gripping reading experience that it turned out to be. I’ll be disappointed if I learn that Ralston had a ghost writer; I want to believe that he can write this well. There’s no reason why not, anyway – he was top of his class at Carnegie-Mellon in mechanical engineering and French, and he has a great memory and a lot of common sense.

Indeed, I think Ralston’s intelligence (along with his top physical fitness) was a big part of what saved him in the end. His engineer’s grasp of basic physics gave him the ability to construct a pulley system (even though it didn’t work, it made him feel like he was moving towards an escape), his outdoor adventures and time with a search and rescue group informed his instincts about threats and aids to his survival, his medical knowledge was sufficient to guide him through a rudimentary surgery on himself, and his ability to recall vivid details of past family occasions and sporting escapades kept his mind on pleasant memories rather than on the obdurate reality of his situation.

Ralston alternates taut present-tense chapters chronicling the details of his crisis with more laid-back chapters recalling other major climbing and skiing exploits from his adventure-filled 27 years (I’m not sure why, but this approach was likened to Tarantino’s films in a number of reviews and in Ralston’s own acknowledgments section). It would be easy to dismiss him as a dumb, foolhardy kid – he was stalked by a bear and almost trapped in a serious avalanche long before he ever entered Blue John Canyon alone – but instead I admired him for his pursuit of the fullness of life. His chapters about climbing and skiing were possibly a bit too technical for laypeople: I tired of the sportsman’s jargon and the names of all the pieces of gear and types of mountain features. Just when I was getting weary of these interludes, about halfway through, Ralston cleverly changed tactics, now devoting the alternating chapters to the nascent rescue attempt, as his family and friends realized he was missing and involved law enforcement and National Park officials.

Even though I knew Ralston would survive, and I had seen a film representation of the grisly method of his escape, I still found the last few chapters very suspenseful. The quality of the writing is such that readers feel they are right there in the canyon with him, trapped and growing more hopeless by the hour. Ralston had written his own epitaph, divvied up his belongings and his ashes through video messages to his family. He was ready to accept death. But then he had a vision – one that was somehow different from his hallucinations of flying up out of the canyon to meet friends, or his so-real-you-could-almost-taste-it waking dreams about ice cold beverages. He saw himself giving a piggyback ride to a little boy, with the stump of his right arm holding the boy steady, and somehow he knew that this was his future son, in their future home. The assurance that he still had life ahead of him gave him the motivation he needed to start the amputation in earnest.

It may sound trite, but ultimately the book was a cogent tribute to the strength of the human spirit. Without a spiritual component to his existence, Ralston could easily have succumbed to dehydration, starvation, hypothermia, or shock. Instead he survived the ordeal, got married and had the prophesied son, continues to climb mountains with a special prosthetic attachment, and travels around giving motivational speeches (for a cool $25,000 a pop). Not bad for a daredevil who made the reckless mistake of going climbing alone without telling anyone where he was heading. Though I don’t think I could ever manage his kind of athletic feats, I do envy him his experiences of pushing his body to its outer limits, and living life right on the knife-edge of death.